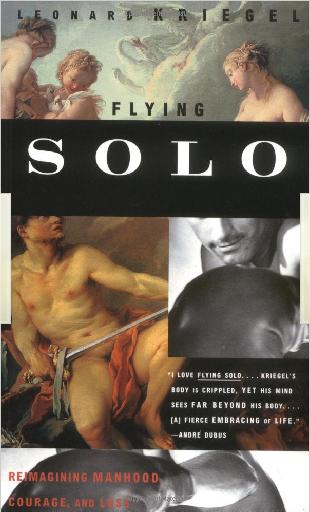

De Amerikaanse schrijver Leonard Kriegel werd in 1933 geboren in New York. Toen hij 11 was werd hij getroffen door polio en sindsdien moet hij gebruik maken van ijzeren beugels om zijn benen en krukken onder zijn armen. Het weerhield hem er niet van een belangrijk schrijver te worden, sterker nog, zijn handicap stimuleerde hem wellicht tot schrijven en die handicap is ook een regelmatig weerkerend onderwerp in zijn essays.

Flying Solo is een bundeling van enkele van die essays. Één ervan – integraal op internet geplaatst – heet “Beaches in Winter”. Het verhaalt van zijn verblijf – samen met zijn vrouw en zoon – in Noordwijk in 1964 in het kader van een Fulbright beurs. Noordwijk confronteert hem met zee en strand en dan ook met zijn handicap. Die confrontatie verandert hem en die verandering is in “Beaches in Winter” mooi – soms ontroerend – beschreven.

Ik jat een stukje van internet:

“I did not begin dreaming of beaches until 1964, a few months after my wife and I and our older son, then three months short of his second birthday, arrived in the Netherlands for a Fulbright year abroad. Housing was in very short supply in the Netherlands in 1964, and two weeks after our arrival we three were still stuck in a hotel room in the Hague, still searching for a place to live. One afternoon we were driven to a seaside village between the Hague and Amsterdam. Noordwijk aan Zee still housed fishermen and tulip growers in 1964, but its chief function now was to serve as a summer resort for vacationing Germans, already the economic kings of postwar Europe. And there we found an apartment facing the beach and the pounding surf of the North Sea.

I had never before lived with a view of beach and water. And I had never before been conscious of the surf pummeling the shore, the way I became two weeks after we moved into that apartment in Noordwijk, when a two-day blow tore into the North Sea coast with awesome power. That Dutch beach was not as attractive as the beach I look down on here in South Carolina or the splendid ocean beaches of New York’s Fire Island. But there was something remarkably seductive about it, some presence that held me, face to the harsh wind, not wanting to surrender the glimpse into my soul living on the beach offered.

For my wife, the beach at Noordwijk was a spiritual sanctuary. Bundled like a Dutch huisvrouw in coat and heavy stockings, kerchief tied around her head as the thrust of wind slashed against her face, she used to go for long walks, alone or with our son. Perhaps because the Dutch were such stolid law-abiding people, Harriet took particular delight in spotting the mast antenna of an illegal radio ship on the horizon— the Dutch gave it the Brechtian name, “Pirate ship Veronica”— swaying in the wind like a drunk on the subway.

(…….)

None of this seems particularly dramatic. Why, then, was it in Noordwijk that I first became a man who dreams of beaches? Is it because the sands of that first beach I lived alongside made life richer and more challenging? Of course, I thought nothing of walking long distances on my braces and crutches back then. Yet will and determination and the strength of my arms were never quite sufficient to master the sand. I knew that. Nonetheless, I tried to master it. I loved that beach as one loves the image of a high school sweetheart. Yet I hated its coarse grittiness. A few miles up the road, the sand was hard and solid and as easy to walk across, even on crutches, as the beach at Daytona. On the beach at Zandvoort, they raced cars. On the beach at Noordwijk, horses and their riders splashed through the sand at low tide.

Whenever I tried to play with my son on the beach, my crutches would sink as if I were on quicksand. The beach at Noordwijk challenged my fatherhood, denied my recurring images of the American man I wanted to be. In my mind’s eye, I would throw my two-year-old son’s legs across my shoulders. As he straddled my neck, imagination would send me running like a fullback straight into the oncoming waves. Or else I would visualize walking across the sand with my wife, pulling her against me, each of us part of the elements— earth, air, fire, water—as we sought love’s promise.”